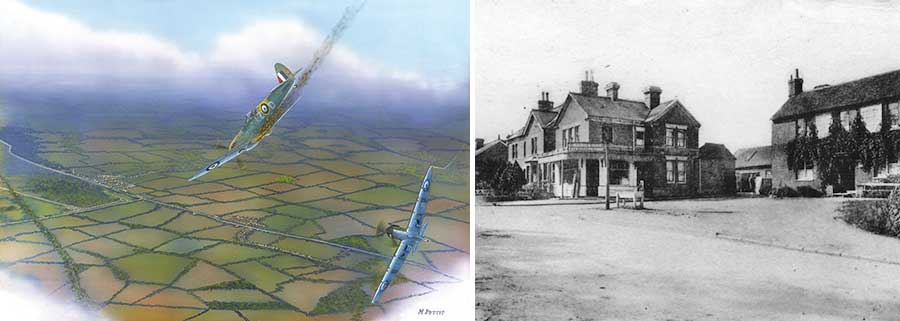

Summer 1940

The boys of bounding high spirits were rather stilled by September 1940, they were strained and silent, but never for a moment did they fail to leap for their Hurricane’s and Spitfire’s like scalded cat’s the moment they heard the dreaded sound of the bell from the telephone to give the squadron the order… scramble.

Scramble was the word used, Victor 1.4, zero Angels 20, those very young pilot’s that had been sitting in their old second hand chairs, or just laying on the grass in the sun that sweltering hot summer of 1940. Wearing their clumsy flying boots, a May West slung loosely upon them, they would just leap onto their feet, colliding with everything in their path, in that mad dash to their fighter, this could be repeated as many as twelve times a day, for those weary and wounded dogged young fighter pilots.

NEVER IN THE FIELD OF HUMAN CONFLICT WAS SO MUCH OWED BY SO MANY TO SO FEW.

How it all began

Growing up in any village, you will always hear stories from the past and all told slightly differently. When I was a young lad growing up in the village of Hildenborough, one story which was often repeated, but rarely differed, was the story of the Spitfire that crashed behind the Half Moon public house during the Battle of Britain. The mystery surrounding why the Spitfire crashed intrigued me throughout my youth. My parents and many other villagers remember that cold and misty morning at about 8.30am on Sunday 27th October, 1940 and hearing a short, but loud burst of machine gunfire, followed by the sound of a screaming Rolls Royce Merlin engine. What happened next is history.

Pilot Officer Johnnie Mather of 66 Squadron was on a routine patrol over Maidstone when he broke formation and went into a near vertical dive. His commanding officer P.O. H. R. Allen saw him break formation, he followed him down, shouting down the RT, “pull out Johnnie, for Christ’s sake pull out”. He then used his surname, “Mather pull out”, by this time the ground was getting very close, too close for comfort, P.O. Allen had to pull out of the dive, as he climbed away he looked back and to his horror, he saw Johnnie’s Spitfire P7539 hit the ground and explode. We can now be 95% sure Pilot Officer R. J. Mather was shot down in defence of London, and not as reported Anoxia.

The mystery and the knowledge of knowing Johnnie’s Spitfire was still there behind the Half Moon, buried in the rear garden, stayed with me and after many phone calls and meetings, in 1972 I finally got permission to recover the Hildenborough Spitfire.

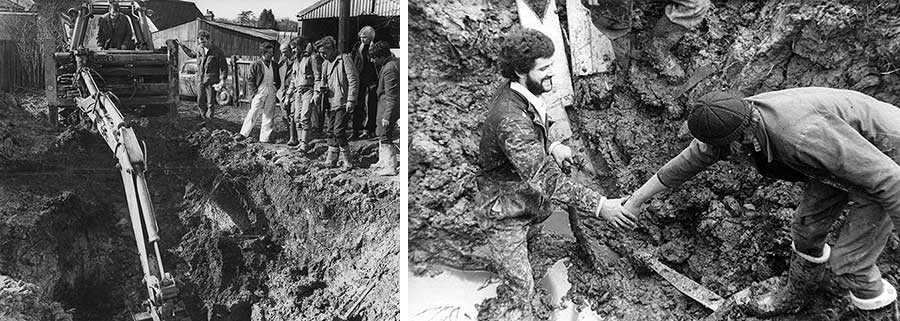

The dig 1972

I managed to organise a group of friends and locals on a cold February morning to start digging for Johnnie’s Spitfire. We started with just shovels and spades, it was hard work, really hard work. After a few weeks we had a lot of help and interest, but work was still slow as we were all still using shovels and spades with the ground hard.

We were never short of friendly advice from villagers who would stop and have a chat, mainly to inform us we were digging in the wrong place and everyone pointed to a different spot! After a few weeks, I managed to persuade local businessman Don King to come along and give us a hand with his JCB, this was a turning point, we quickly start to make ground and at about 15 feet down we could clearly smell aviation fuel and oil, nobody could light up a cigarette, we found railway sleepers and sacking which had been left from the original RAF recover unit in 1940 and just a little further down we finally found the Spitfire engine. This is what I had been wanting to find for so many years and finally finding Johnnie’s Spitfire was very emotional.

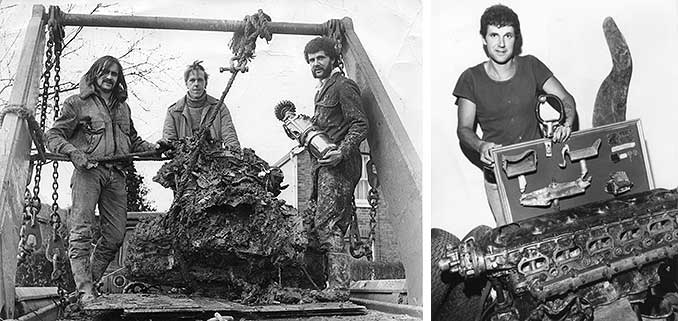

Although we had found the engine, we had one problem, we couldn’t move it. The engine was stuck fast in the wet mud, nothing would break it loose, not even the JCB. Don King came up with the solution, “use my skip lorry”, we managed to get a rope around the Spitfire engine and used the lifting arm of the skip lorry and slowly the engine broke free from its resting place for 32 years and came out like a rotten tooth. Although the engine was in relatively good condition for what it had been through, we managed to recover a few other items, the Coffman starter motor, Supermarine rudder pedals, various parts from the instrument panel, cockpit glass and many other small artifacts.

Finding the missing

Having recovered Spitfire P7539, I wanted to find others which had been forgotten or lost. So I started researching and digging local crash sites. Although we found a few sites, these were generally well known and any artifacts generally already removed. I then met Al Brown. Al was brilliant at research, he would spend hours, days at the Public Records Office at Kew in London, researching missing aircraft and local news stories from that time. Al’s diligence was priceless, over the coming years we were able to find many missing aircraft and pilots.

We became more determined to find the missing pilots from the Battle of Britain, those who had been forgotten. But sadly, the more we recovered, the more the Ministry tried to stop us. We were told that the Ministry had not got the funds to give these pilots a burial and they would do everything to prevent us from recovering them. But we continued with the same determination to find any missing pilots and aircraft we could and over the years I was involved with about 25 recoveries.

The museum today

The museum today has items from over 40 different crash sites recovered from the Battle of Britain, many with historical importance. The museum is a collection of historical artifacts I’ve collected over the last 43 years, a record to those brave young men who fought and won against the odds. I have added some of their stories to this website, you can read their stories in the The Few section.

One of the aircraft I recovered was Spitfire P9372 of 92 Squadron Biggin Hill, this aircraft was damaged in the Battle of France over Dunkirk and shot down during the Battle of Britain on the 9th September, 1940. P9372 was flown by Pilot Officers Tony Bartley and later Bill Watling of 92 Squadron. I have now sold P9372, which included the aircraft identification plate, to Peter Monk of the Heritage Hanger at Biggin Hill. Peter has since sold the aircraft himself to a wealthy businessman and Peter has been commissioned to rebuild P9372 to airworthy condition. To see P9372 fly again would be truly wonderful, to see an aircraft I recovered fly again, really makes the last 43 years worthwhile.

I hope you find my story, the pilots stories and museum of interest, this is my “tribute to the few”.

Malcolm Pettit